Gender Bias in Class 8 Bihar Textbooks

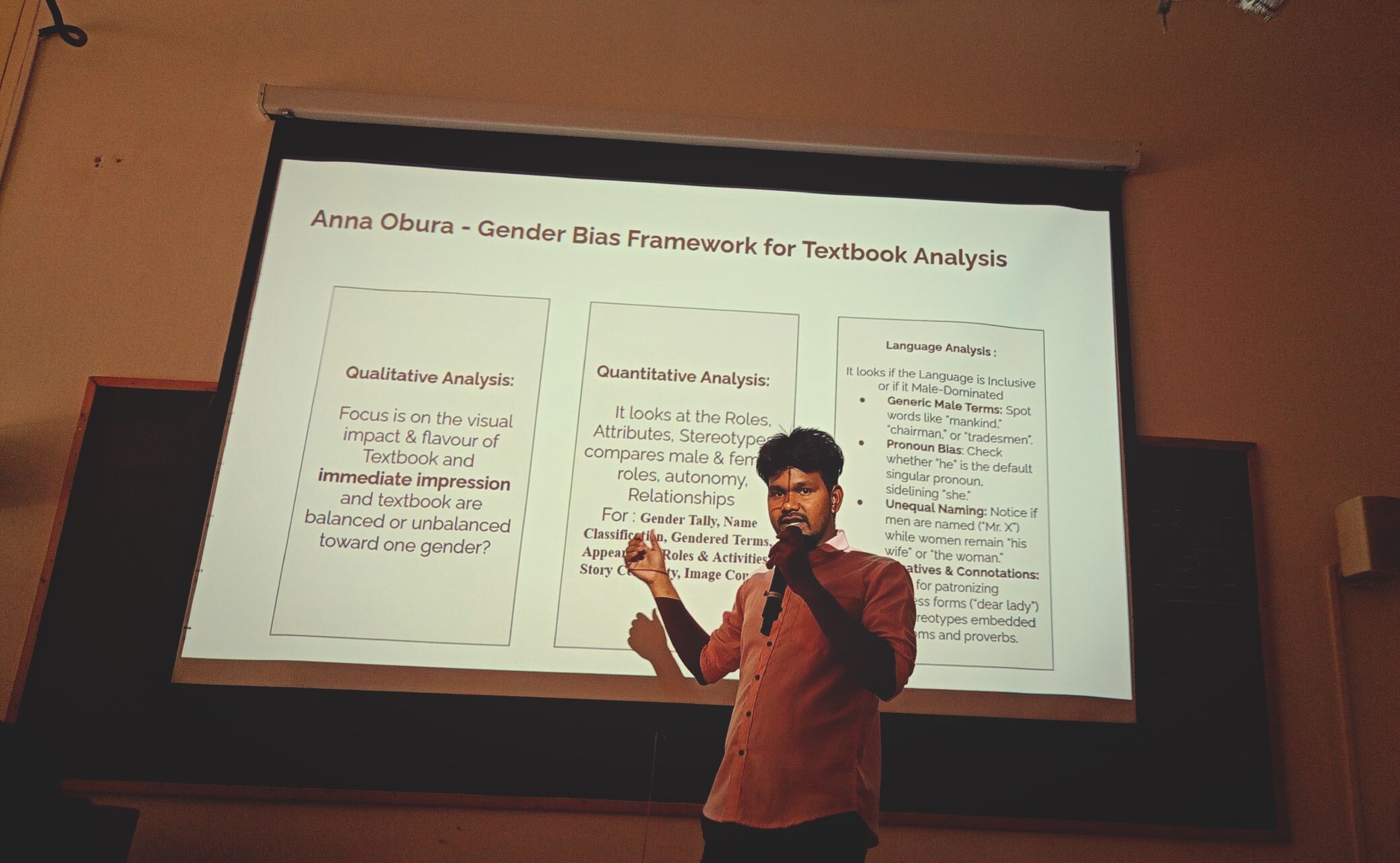

A few days back, I presented a systematic, qualitative gender-bias analysis of Class 8 history textbooks used in Bihar schools. Using Anna Obura’s framework, I examined not just whether girls appear in textbooks, but how they appear—through visuals, roles, language, and agency. The goal was simple: move beyond counting illustrations and instead understand how textbooks shape the way young learners see girls, boys, leadership, and possibility.

What I Found: Three Layers of Hidden Bias

Visual Messages Matter

When I examined the illustrations in Hindi textbooks, patterns emerged quickly. Girls appeared in less than 20% of all images. More striking was what they did in those images. They stood by. They listened. They helped with domestic work. Boys filled the action scenes. They led. They fought. They discovered. They made decisions.

This visual imbalance teaches a lesson. It whispers to every student: boys belong in public life, in positions of power. Girls belong in private spaces, in supporting roles. Students see this message hundreds of times. Eventually, they believe it.

Roles and Relationships Tell a Story

The roles given to characters revealed more bias. Male characters led movements. They innovated tools. They negotiated treaties. They made choices that mattered.

Female characters did different work. They assisted. They supported. They observed. They were defined by their relationships to men—”daughter of,” “wife of,” “sister of.” Their own identities disappeared. Their own achievements faded into the background.

This pattern sends a message: women matter through their relationships to men. Women matter because they care for men. Women matter only when connected to men. Students absorb this lesson slowly, then fully. It shapes how they see themselves and what they believe they deserve.

Language Shapes How Children Think

The words used in these textbooks matter enormously. Over 80% of narrative pronouns defaulted to “he” or male-generic terms like “mankind.” The verbs differed too.

Descriptions of girls used passive language: “was taught,” “was guided,” “was shown.” Descriptions of boys used active language: “led,” “fought,” “discovered,” “spoke.” Language does not just describe action. It shapes how brains process information. When girls rarely “act” in stories, their brains learn that action is not their role.

Why This Matters for How Children Develop

This research matters because textbooks change children’s brains. They change what children believe about themselves.

When girls read textbooks showing girls as passive, their confidence drops. Research confirms this. Girls taught with biased materials try less hard in difficult subjects. They avoid challenging tasks. Over time, they stop raising their hands in class. They choose easier paths.

This happens through self-efficacy—your belief in whether you can do something. When a girl reads that girls never lead or solve problems, her brain accepts this. She believes leadership is not for her. She believes problem-solving belongs to boys. This belief then changes her choices. She avoids science classes. She skips math. She does not volunteer for leadership positions.

The impact follows her into adulthood. Girls who read these textbooks pursue different careers. They avoid science, technology, and leadership fields. More concerning, they accept gender inequality as normal. They accept that some things are just “for boys” or “for girls.” This normalization can lead to acceptance of dowry, of inequality, of discrimination.

Breaking Down the Hidden Curriculum

Qualitative analysis reveals what counting cannot. Yes, girls appear in 20% of images. But that number hides the real story. The real story is in what those girls do. The real story is in which characters make decisions. The real story is in whose achievements matter.

Anna Obura’s framework helps us see layers of bias. One visual of a girl in a passive role is not catastrophic. But multiply that by hundreds of pages. Multiply it by years of schooling. Now add the passive language. Add the relational labels. Add the male pronouns. The layers combine. They create a powerful hidden curriculum that teaches girls who they are supposed to be.

This is why qualitative analysis is essential. Numbers alone miss the truth. The truth lives in details—in verbs, in relationships, in whose story gets told.

How We Can Change This

Based on my research and what education experts have found, here is what needs to happen:

Textbook Publishers Must Rewrite Stories, Not Just Add Pictures

Simply adding more illustrations of girls does not solve the problem. Publishers need to rewrite the actual stories. Show girls leading movements. Show girls negotiating, fighting for justice, making discoveries. Use active language: “She led,” not “She was involved.” Include women’s achievements as main stories, not as special boxes or footnotes. Show girls and boys in all kinds of roles—as soldiers, as scientists, as leaders, as thinkers.

Teachers Can Counter Bias in the Classroom

Teachers have power that publishers sometimes underestimate. When you notice a bias in your textbook, talk about it with students. Ask them: “Why do you think this book shows only boys as leaders? What would a girl who lived then have done? What would she have wanted?” These conversations help students recognize that textbooks are not neutral. They teach critical thinking. And they offer students alternative role models and stories that go beyond what the book presents.

Education Policy Must Make Bias Analysis Mandatory

Right now, textbooks are approved based on what? Content accuracy, alignment with curriculum standards—but rarely based on a careful examination of gender bias. This needs to change. Before a textbook is approved for use in schools, it should undergo a qualitative gender-bias analysis. This analysis should examine visuals, language, agency, and how characters are framed. Not just counting, but understanding. Education officials need to set standards that require diverse, active representation of all people across history and all subjects.

Researchers Must Continue This Work

I also want to say that this kind of research is crucial. We need more qualitative studies that examine how textbooks actually shape children’s thinking. We need this research to reach teachers, principals, parents, and policymakers. We need them to understand that textbooks are not passive information containers. They are tools that actively shape how children see themselves and what they believe they can become.

What I Learned From This Analysis

When I conducted this research and presented it to my colleagues, I realized something important: most people do not think about textbooks this way. They think textbooks are just books. But textbooks are among the most powerful educational tools we have. They are often the only books some children own. They are used for hours every day, year after year. The messages in textbooks, especially the hidden messages, become part of how children think.

The girls in Class 8 who read these textbooks every day are absorbing messages about their own capabilities. When they see girls only in passive roles, they are learning something about what is possible for them. When they see boys leading and deciding, they are learning something about who gets to lead and decide. These are lessons that will follow them into college choices, career decisions, and the kind of lives they imagine for themselves.

A Call to Action

If you are a textbook publisher, I am asking you to look carefully at what you are publishing. If you are an educator, I am asking you to be aware of what your textbooks are teaching beyond the official curriculum. If you are a parent, I am asking you to talk with your children about what they are reading and who they see represented as leaders and thinkers. If you are a policymaker, I am asking you to make gender-bias analysis a requirement before textbooks are approved.

Textbooks shaped the minds of previous generations. They are shaping the minds of the current generation of students in Bihar and across India. If we want a generation that believes all people—girls and boys equally—can lead, discover, and change the world, we need to change what we put in textbooks. We need to make sure that every student who opens a history book sees themselves reflected as an active, capable, important person in the story of human progress.

That is why this work matters. That is why I continue to do it.

Key sources and links that support the points we discussed:

On Gender Bias in Textbooks and Hidden Curriculum:

- UNESCO Support for Girls in STEM: https://unesdoc.unesco.org

- The Silent Curriculum: How Hidden Pedagogies Influence Student Development: https://rsisinternational.org

- Hidden Curriculum: The Unspoken Messages Students Receive: https://varthana.com

On Self-Efficacy and Student Learning:

- Academic Self-Efficacy from Educational Theory to Instructional Practice: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Self-Efficacy in Learning Research: https://cambridge.org

On Gender Bias in STEM and Career Aspirations:

- The Gender Gap in STEM Fields: The Impact of Gender Stereotypes: https://frontiersin.org

- Impact of Gender Role Stereotypes on STEM Academic Performance: https://aimspress.com

On Teacher Bias and Learning Outcomes:

- Biased Teachers and Gender Gap in Learning Outcomes: https://sciencedirect.com

On Gender Analysis in Education:

- ABC of Gender Analysis: https://ccgdcentre.org

- Practising Gender Analysis in Education: https://econtent.hogrefe.com

On Textbook Analysis:

- Gender Bias in Textbooks: Uncovering Hidden Stereotypes: https://yoursmartclass.com

- Analysis of Gender Stereotype in Chinese Textbooks: https://thelawbrigade.com

- Gender Bias in the Curriculum: https://atlantis-press.com

On Indian Textbooks:

- Department of Gender Studies Analysis of Textbooks: https://n20.ncert.org.in

- Bihar SCERT Class 8 History: https://testbook.com

- NCERT Solutions for Class 8 Social Science: https://vedantu.com